7 Books 7 Days: Tuesday’s Book

A Descriptive Bibliography of the Works of Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772)

3 volumes (volumes 4 and 5 in preparation)

(London: Swedenborg Society, 2010-)

As an independent and specialist publisher, one of the areas in which the Swedenborg Society has been the leader in its field has been in producing enduring and durable reference works to aid scholarship and researchers. Norman Ryder’s BIBLIOGRAPHY is the perfect aid to Swedenborgian academics, librarians, editors and bibliophiles, but pore through its contents and there are many interesting stories waiting to tumble out of the resolute blue buckram covers to be further explored by experts and curious laypersons alike.

For example, looking solely at records of Swedenborg’s most popular work, Heaven and Hell (1758), in volume 3 of the BIBLIOGRAPHY, we discover that a 1925 German abridgement, entitled Himmel Hölle Geisterwert, was edited and introduced by the poet, playwright, actor and scriptwriter Walter Hasenclever (1890-1940), who sadly committed suicide in a French camp for ‘foreign enemies’ to avoid falling into the hands of the Nazis, who had just occupied France, and who had banned Hasenclever’s books a few years earlier in 1933. It is through Hasenclever and his interests in the esoteric and spiritual that Swedenborg can be tied to the German expressionist cinema of F W Murnau and others—Hasenclever’s former girlfriend, Greta Schröder, starring in Murnau’s silent classic Nosferatu (1922), and her later husband, Paul Wegener, co-directing and starring in The Golem: How He Came into the World (1920).

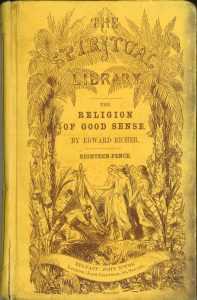

Combing through the BIBLIOGRAPHY, we find that only one edition of Swedenborg seems to have ever been produced from Ireland, the 1853 book The Future Life, which is an edition of a Swedenborg Society translation of Heaven and Hell, revised, retitled and printed by John Simms in Belfast and J M’Glashan in Dublin. The revision was once attributed to Speranza, aka Lady Wilde (mother of Oscar Wilde), and the confusion seems to have arisen because The Future Life was the third volume of a series called ‘The Spiritual Library’, produced in distinguished illustrated yellow board covers, established by the publisher John Simms. The first two volumes in ‘The Spiritual Library’ series (and indeed a planned but never issued fourth volume) were by the Nantes-based writer Edouard Richer (1792-1834)—his name anglicized to ‘Edward’ by the publisher—and these were indeed translated from the French by Lady Wilde.

Other interesting translators include Habib Anthony Salmoné (1860-1904), who translated Heaven and Hell into Arabic for the Swedenborg Society in 1896. Salmoné was a writer, Orientalist scholar and professor of Arabic at King’s College London. He compiled a 2-volume Arabic-English dictionary and was an intelligence informant to the British Foreign Office around the time of the Siege of Khartoum (1885). His association with the Swedenborg Society presumably came via his friend, the prominent Swedenborgian author and homoeopathic physician, J J G Wilkinson, who lists Salmoné in his address book (another gem of an item in our archive!).

Then there is Aleksandr Nikolaevich Aksakov (1832-1903), Russian spiritualist, author, Imperial Councillor to the Tsar, and the person said to have coined the word telekinesis, who produced a Russian translation of Heaven and Hell in 1863, although it was published in Leipzig, Germany to avoid censorship. This edition was read by Dostoevsky, influencing Crime and Punishment and The Brothers Karamazov.

And an 1899 translation into Gujarati was produced by the scholar Manishankar Bhatt (1867-1923), who helped set up the Swedenborg Society of India and is perhaps better known by some as a poet who wrote under the pseudonym of Kavi Kant. His innovative volume of poems, Purvalap, was published on the day of his sudden tragic death in a railway carriage at Lahore station, whilst he was away on holiday. Bhatt had been travelling alone and his family didn’t learn of his passing for several months.

The BIBLIOGRAPHY can lead one down avenues of enquiry that uncover some fascinating life stories connected with the history of publishing Swedenborg—none more so than that of Swedenborg himself. Swedenborg wrote a prodigious amount of published and unpublished material (Norman classifies the output into 257 titles, some of those multi-volume and hundreds of pages long!) on a vast array of disparate subjects, and the BIBLIOGRAPHY, with its helpful overview in volume one of Swedenborg’s literary corpus, is one of the best ways of grasping the entirety of Swedenborg’s life as an author.